Nantucket Today

November/December 2005

Portrait of an Artist: MJ Levy Dickson

STORY AND PHOTOGRAPHY BY TERRY POMMETT

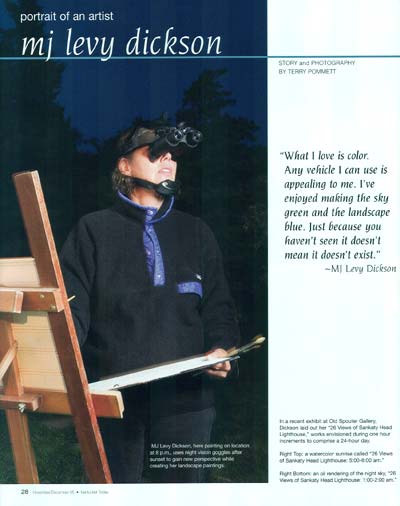

MJ Levy Dickson, here painting on location at 8 p.m., uses night vision goggles after sunset to gain new perspective while creating her landscape paintings.

The world became accustomed to a new form of imagery during the Afghan and Iraqi invasions. Video feeds for television and the Internet utilized night vision technology, transmitting images of shimmering shapes tinged in a ghoulish green, interrupted by sudden bursts of light. The scenes they portrayed appeared radioactive and unnatural. For Nantucket artist MJ Levy Dickson, however, the artistic implications of seeing the world through such an intimidating “looking glass” were provocative and compelling.

“At the time I had been doing sunrise and sunset paintings, where everything was silhouetted. I tried using night vision goggles to see beyond the fading light. It pushed my work to another level. But it was something I had to adjust to, knowing how the technology is primarily used. I watched the fireworks a couple of years ago with the goggles and it was frightening. It was very uncomfortable and reminded me of war. I prefer trying to use them in an artistic sense,” she said.

Dickson’s most recent exhibit, “26 Views of Sankaty Head Lighthouse” at Old Spouter Gallery, included a number of her night vision renderings. The show was a reflection on the passage of time, space and light where the venerable Sankaty lighthouse was the central subject, caught in each of 24 hours in the day from different viewpoints and in varying weather conditions. The minimalist impressions, rendered in a variety of mediums- oil, watercolor, charcoal, ink and print-making – capture the threatened landmark in its quiet, solitary strength. The works are enduring and spiritually reflective.

“What I loved about the Sankaty series was watching the sun rise and then seeing how the color evolved during the day. When I finally laid out everything in the studio, it had a cohesion, a series with an order to it. I could see the course of a day,” Dickson said.

Dickson’s landscapes are a departure from her formative training. The youngest of three children, whose mother showered her with pencils and crayons to keep her occupied, she is no stranger to museums or the discipline of art school.

“The Museum of Fine Arts held children’s art classes on Saturday mornings, which I attended. I loved walking through the corridor lined with Colonial portraits where the eyes seemed to follow you. It was exciting and scary. From then on, art was always my favorite subject in school,” she said.

After receiving her bachelor’s degree in fine arts from a joint Tufts and Museum School program in 1973, Dickson went to work for Sasaki Associates, an architectural firm in Watertown, Mass. Her talents were applied to architectural drawings where, in a pre computer age, presentations had to be visualized and drawn by hand. “I loved my work, putting in trees and landscaping, how buildings related to each other. What helped sell a project was the feeling behind it. You had to make something look like it fit,” she said.

Throughout her stay in the Boston area, Dickson and her fiancée, Tom, had been considering a permanent move to Nantucket. Following their marriage in 1979, the first ever wedding on the public viewing area of the World Trade Center (“We had to get married at 9 a.m. before all the tour buses unloaded”), the couple bought a cottage in Sconset.

Right Top: a watercolor sunrise called

"26 Views of Sankaty Head Lighthouse: 5:00-6:00 am."

Right Bottom: an oil rendering of the night sky,

"26 Views of Sankaty Head Lighthouse: 1:00-2:00 am."

Beside the raising of her two children, Aaron and Graham, Dickson’s time was consumed with her artistic development. She rebelled from the art school mentality that had guided her earlier painting. “When I was younger and less confident, I was overly concerned with literary themes: tension, conflict and resolution. I did technically more challenging work. Not knowing how people would respond, I felt I needed to show my training as an accomplishment.”

Abandoning a pre-conceived notion of what her art should include has liberated Dickson’s subject matter, palette and style. Her work cannot be categorized with familiar artistic terminology. It is constantly evolving. Impressionist, Abstract, Cubist, Realist. The terms all apply and overlap, but do not define her work. There is mystery and movement in her oils and watercolors; nothing is static. Landscapes are open and airy, sometimes brooding, often joyous, never overloaded with detail, yet very suggestive and complete. Skies are as prominently featured as the earth, but not in a splashy sense: subtle, dreamy and complex. They are tone poems of color.

“What I love is color. Any vehicle I can use is appealing to me. I’ve enjoyed making the sky green and the landscape blue. Just because you haven’t seen it doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist. The landscape has become my vehicle and the colors are the subject matter. I prefer color to words. It’s easier for me,” Dickson said.

Sketching during musical events is a Dickson pastime. She loves to draw while attending the Boston Symphony, capturing conductors on the pages of her program. She has also compiled an impressive series of drawings executed during the New Orleans Jazz Festival. “Sketching is a first step for me in preparing for a statement,” she said.

Beyond her love of family and art, teaching has been the most constant and satisfying element of Dickson’s life. She began giving drawing classes at the Boston Architectural Center in 1975. “That was my first teaching job. It was a way of giving back. All my teachers worked hard with me, especially my mentor, Jan Cox. I had acquired so much knowledge from them that I wanted to pass it along.”

She has worked with students from MIT and Lesley University and continues to teach privately and at the Montessori school on Nantucket. However, for close to 30 years her passion has been to bridge the gap between verbal and visual appreciation for art.

“Understanding art is not about education but about understanding your own feelings. Feelings are valid. You don’t have to know the name of a painting or the artist to appreciate it. In the West, we verbalize our thoughts much more than visualizing them. I teach because I don’t want people to be intimidated with art. The playing field I like to establish is “How do you feel?” How the painting makes you feel is what is important.”

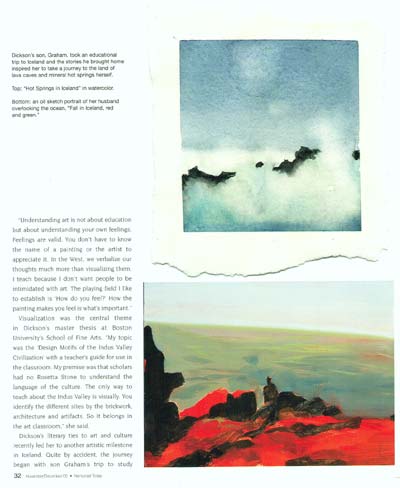

Dickson's son, Graham, took an educational trip to Iceland and

the stories he brought home inspired her to take a journey to

the land of lava caves and mineral hot springs herself.

Top: "Hot Springs in Iceland" in watercolor.

Bottom: an oil sketch portrait of her husband overlooking the ocean,

"Fall in Iceland, red and green."

Visualization was the central theme in Dickson’s master thesis at Boston

University’s School of fine Arts. “My topic was the ‘Design

Motifs of the Indus Valley Civilization’ with a teacher’s guide

for use in the classroom. My premise was that scholars had no Rosetta Stone

to understand the language of the culture. The only way to teach about the

Indus Valley is visually. You identify the different sites by the brickwork,

architecture and artifacts. So it belongs in the art classroom,” she

said.

Dickson’s literary ties to art and culture recently led her to another

artistic milestone in Iceland. Quite by accident, the journey began with son

Graham’s trip to study underground volcanoes with Earth Watch. After touring the Snaefellsnes Peninsula

with his father, Tom, the two returned to Nantucket with inspirational stories

for mom. “My first experience with Icelandic culture occurred in 1982

when I saw an exhibition of the ‘Illuminated Manuscripts of Iceland’

at the Pierpont Morgan Library. It seemed like a fascinating place no one

ever talked about. So I was eager to see the country, she said.”

The Snaefellsnes Peninsula is two hours from Reykjavik and is the heartland of Icelandic history, home to many important sagas and natural beauty. It brims with lava caves, rock formations, waterfalls and mineral hot springs. “The place took me by surprise. It was the same type of feeling I got stepping off the boat in Nantucket. There are a number of similarities between the two places,” Dickson said.

After completing a few paintings on location, Dickson approached Elinbjort Jonsdottir, owner of Galleri Fold, and was given space to exhibit. Because of the connection Dickson felt between Iceland and Nantucket, the show was entitled “First Impressions: Different and the Same.” It consisted of all small works and was very well received. “There is a poetic nature to the Icelandic people that you feel right away and discover in conversation. They live on the edge between their souls and their experience. I received a number of compliments from people who were surprised I wasn’t an Icelandic painter. One man told me he thought my work was very smart, which I later learned meant ‘intelligent.’ I had never before heard anyone describe my work that way,” she said.

The people really enhanced the physical beauty of the country and how I perceived it. They have a belief in elves and trolls and will talk about their legends if they know you’re sympathetic to what they have to say. It all added to the mystery of the place. Elinbjort helped open up the culture for me and has inspired me to return someday for another exhibit.”

On the home front, Dickson continues to be a stealth force within Nantucket’s artistic community. What is so engaging about her work is that it is unpredictable. From one project to the next her production is less about familiarity than it is about discovery and immediacy. From detailed drawings of wildflowers to abstractions of skate eggs and seaweed, from sketches of musicians to ethereal skyscapes, Dickson’s focus becomes a statement that needed to be made.

Always getting ready for her next artistic journey, Dickson is fond of sketching at live musical performances, such as this pen and ink and watercolor wash impression entitled “New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival 2005: Fais Do-Do Stage.”

“I’m always looking in different directions. I have enough work in my mind to last a lifetime. It’s just a matter of where to show it, who to prepare it for. And I have help. When I’m not sure if something is working I call my daughter, Aaron, in New York City. As a fashion designer, she has a great eye and is sure of her opinions,” she said.

Future projects on the Dickson horizon include a series of surfing paintings inspired by son Graham, a tree study, and war. “I’m amazed at the spectacular colors at sunset with the action of the surfers and waves. I also want to explore a particular tupelo tree off the Polpis Road, that grows horizontally. I want to capture it at different times of day and using a night vision palette and different media.

“Because of my night vision experiments, I’ve been encouraged to paint about war. I’m concerned with desperation in the world, the feeling of having no hope. I don’t look for beauty in war, but for the beauty of resolution that follows conflict. I hope to draw people’s attention to something they might not have considered.”

In that regard, Dickson is working toward producing a series of cards based on her sketches at the New Orleans Jazz Festival. All proceeds will go to aid the victims of Hurricane Katrina.

MJ Levy Dickson’s work can be viewed at Old Spouter Gallery, Nantucket Looms and the Artists’ Association of Nantucket. In addition, Peter Dunwiddies’ “Wildflowers of Nantucket” guide, available at island bookstores, showcases her beautiful pen and ink watercolors.

Terry

Pommett is a photojournalist living

on Nantucket.